KONG Tianping:The 16+1 Framework and Economic Relations Between China and the Central and Eastern European Countries

The formation of the 16+1 framework is one of the most important achievements of China’s diplomacy. The ‘16+1’ framework refers to different mechanisms and arrangements between China and 16 Central and Eastern European countries that were formed after Premier Wen Jiabao’s historic visit to Poland in 2012. Since then, the 16+1 cooperation framework has been widely accepted in Central and Eastern European countries and has moved on a fast track. In the last two years, summits between China and the Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) have been held on a regular basis, with different cooperation mechanisms formed or under consideration. Contrary to China’s unilateral “12 measures,” the Bucharest Guidelines and the Belgrade Guidelines became a joint pledge for cooperation.

Mutual efforts by China and the CEEC have drawn relations closer. From China’s point of view, the CEEC, especially the new member states of the European Union (EU), can play an important role in Europe; the CEEC can serve as China’s bridgehead for exploration of the European market. Although the CEEC suffered from the global financial crisis and euro-zone debt crisis, these countries have shown resilience. From the perspective of the CEEC, China has become an important factor in a global shift of power: it has maintained a good record of economic growth; its economic clout continues to expand; and it should be regarded as an important economic partner for the CEEC.

China’s rise as a powerhouse of the world economy is one of the most important factors in the global power shift. Fast-paced economic growth and the improvement of people’s welfare can be attributed to a sound economic reform strategy and economic policy, opening to the outside world, and active participation in the process of globalization over the last three decades. In 2010, China overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy by nominal GDP. China is now a global hub for manufacturing and the largest manufacturing economy in the world. Most importantly, reform set the depressed entrepreneurial spirit free: innovative and competitive enterprises came into being, have moved up the value chain, and have competed within China and elsewhere around the world. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization at the end of 2001 was also a milestone that drove the growth of foreign trade. Additionally, in 2002, the “Go Global” strategy, in which Chinese government encouraged Chinese firms to explore the global market, was put forward.

However, after the global financial crisis, China’s foreign trade slowed down substantially. China’s imports and exports decreased by 13.9% in 2009 as China felt the pinch of the crisis. Then, as the world’s largest and second-largest importer, China became a trading power. As the value of China’s exports and imports reached $4.16 trillion in 2013, China overtook the US to become the world’s largest trader of goods for the first time. As China is fully integrated within the global economy, the CEEC as part of emerging European economies cannot be neglected for long. The global financial crisis has accelerated China’s maneuver in the CEEC.

Central and Eastern European countries suffering from the global financial crisis turned to China for economic cooperation and trade promotion. When Viktor Orban came into power in 2010, Hungary introduced a more open policy to the East. When Premier Wen visited Hungary, Prime Minister Orban expressed Hungary’s readiness to act as a long-standing economic, financial, and logistic foothold in the Southeast European region. Some Central and Eastern European countries reiterated their ability to serve as China’s gateway to markets in the EU, the world’s largest economic block. As a consequence of the global financial crisis, especially the Euro-zone debt crisis, the waning demand in the West compelled firms to look for a market outside Europe, and China, one of the largest emerging markets, was regarded as an option.

BorsodChem Rt.

At that point, Central and Eastern European governments actively sought a way to deepen economic relations. For example, Poland launched the “Go China” strategy aimed at encouraging Polish entrepreneurs to cooperate with Chinese business partners and explore the booming Chinese market. The China Investment Forum held in the Czech Republic aimed to boost economic relations between China and the Czech Republic. In the last three years, both political leaders and business leaders have demonstrated a willingness to develop economic and trade relations: the window of opportunity has opened.

During this opening process, the 16+1 cooperation framework has evolved in the direction of loose institutionalization. The institutional arrangement in different mechanisms is not tight-knit—each country or entity can decide whether or not to join the relevant mechanism for cooperation on a voluntary basis. The China-CEEC Summit, i.e. the China-CEEC leaders’ meeting at the prime minister level, is held yearly. The China – Central and Eastern European Countries Economic and Trade Forum is held on an annual basis. Before the summit, a national coordinators’ meeting is held to coordinate positions and prepare for the summit. It should be noted that progress has been made in the institutionalization of cooperation mechanisms in various areas, and institutionalization in different areas usually takes the form of an association, a forum, or a networking opportunity, which can facilitate contacts between China and the CEEC. For example, Hungary hosted the China-CEEC Association of Tourism Promotion, Institutions and Travel Agencies, and Serbia will set up a China-CEEC Federation of Transport and Infrastructure Cooperation. The executive office of the China-CEEC Joint Chamber of Commerce will be stationed in Warsaw, and the secretariat of the China-CEEC Contact Mechanism for Investment Promotion Agencies will be established in Beijing and Warsaw. Bulgaria will host the China-CEEC Federation of Agricultural Cooperation; The Czech Republic will host the China-CEEC Federation of Heads of Local Governments; and Romania took the initiative to set up a China- CEEC Center for Dialogue and Cooperation on Energy Projects. These different federations can serve as a social network capital, and if those mechanisms are given full play, the economic relations between China and the CEEC can be further strengthened.

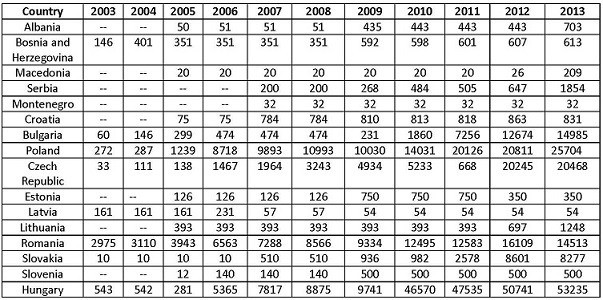

Trade and investment is high on the agenda in the 1+16 framework. The last decade has seen rapid growth in trade between China and Central and Eastern Europe: the trade volume between China and the CEEC in 2014 reached $60.2 billion, five times more than in 2004. During the Bucharest Meeting, China and the CEEC set the goal of doubling trade volume over the next five years. According to the 2013 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), China’s outward FDI stock in the CEEC amounted to $1401 million, while China’s outward FDI stock in the EU-15 reached $38.5 billion. This shows that China’s investment in the CEEC is relatively insignificant.[1] Since 2004, China’s firms have started to enter the CEEC, coinciding with EU’s largest enlargement in the CEEC. The activity of acquisitions by China’s enterprises is concentrated in the Visegrad Group while the main infrastructure projects are located in West Balkan states. There are some visible investment cases in the CEEC; for example, Wanhua Industrial Group acquired full control over the Hungarian chemical company BorsodChem in a transaction of $1.69 billion in February 2011. LiuGong Machinery Corporation finalized its agreement to acquire Poland’s Huta Stalowa Wola (HSWS) and its distribution subsidiary Dressta Co, Ltd. in January 2012. China Railway Signal & Communication Corporation has signed a deal to buy a majority stake of 51 percent in the Inekon Group from its founder Josef Hušek. Inekon, a Czech tram producer, will thus receive a marked financial boost and a strong foothold in the Chinese market. Rizhao Jin He Biochemical Group (RZBC) announced in Budapest in 2014 that it had chosen Borsod County in Hungary as the site of a new citric acid factory, with sales planned for the European market. China’s preferred countries for loans are Macedonia, Serbia, and Montenegro, as these countries can provide sovereign credit guarantees. The Zemun-Borca Bridge in Belgrade, valued at $260 million and built by China Road and Bridge Corporation, has already been completed, while a section of the Corridor 11 Highway (valued at $334 million) being built by Shandong Highway Corporation is underway. It should be noted that there has not been much green-field investment or brown-field investment from China in the CEEC in last couple of years, a source of disappointment for some Central European countries.

China, as a latecomer on the CEEC market, faces the reality of a saturated market as Western European firms already predominate. Because China’s firms lack experience in international business and know less about the business culture and business practices of the CEEC, business decisions regarding investment are time-consuming and difficult. The 16+1 framework will help Chinese firms a great deal as it facilitates business contacts, builds social networks, and makes business decisions easier.

China’s Outward FDI Stock in Central and Eastern European Countries (unit: 10000 USD)

Tianping chart 1Source:Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, National Bureau of Statistics of China,State Administration of Foreign Exchange, 2013 statistical bulletin of China’s outward foreign direct

investment, China Statistics Press, September 2014.

(Contant Kong Tianping:kongtp@cass.org.cn)